1993 – Science can be fun and feminine

Caroline Smith - Science Teacher

St Catherine's News 1993

An appreciation of science also develops our ability to make informed rational judgments and to think critically and logically and enables us to understand better the major issues which confront us in our technologically based society.

To compete in today’s world we must have some understanding of science.

An appreciation of science also develops our ability to make informed rational judgments and to think critically and logically and enables us to understand better the major issues which confront us in our technologically based society.

Physical sciences, in particular, have become a prerequisite for many tertiary courses. Students must study them if they are not to be disadvantaged in the career market.

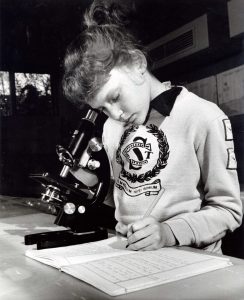

Work with a microscope can be fascinating. . . as Jane Jedwab ( Year 7) science student, is discovering here.

Women are poorly represented in the sciences and technology. Only about 10 percent of physics teachers and one percent of engineers are women. In chemistry the record is better, but women are still under-represented in the chemistry-related professions.

Last year in Victoria, only 25 percent of HSC physics students were female, even in girls’ schools where the social pressures not to take physics are less strong.

Science still has a masculine image. This becomes a particular problem around the time of adolescence — the very time girls are making decisions about the subjects they wish to study.

Socialisation of girls gives rise to a sense of incompatibility between being feminine and achieving in “masculine” subjects such as mathematics and physical sciences.

There are many reasons for this image. The stereotype scientist is a man in a white coat working with equipment; science textbooks show boys performing experiments.

A female scientist is typically portrayed as unattractive — an unappealing image for adolescent girls preoccupied with looks, fashion and the need to be seen as attractive.

Traditional teaching of science has also helped alienate girls. They do not relate to the dry, rigid manner in which science is often presented. Even examples used to illustrate concepts — the workings of a car engine or the mechanics of a bullet fired from a gun — do not appeal to the majority of girls.

Physics, more than other branches of science, has concepts which many students find difficult to integrate into their existing conceptual frameworks, leading to misconceptions and confusion.

The subject is then perceived as difficult and irrelevant, and there is, for girls, little motivation to pursue it.

How can science education encourage the participation of girls?

First, the curriculum is being examined with a view to making science more society-based and, hence, human-centred. Second, strategies for science teaching are being examined. This, of course, has immediate implications for the science teacher.

The Melbourne-based McLintock Collective, a group of science teachers interested in teaching strategies, is working to develop, produce and trial teaching materials.

Girls relate well to human centred activities, hence the popularity of biology. They have well-developed verbal skills compared with boys, and enjoy activities which involve creative expression, such as writing, poetry and drama.

Girls participate well when co-operative rather than competitive strategies are used.

Such strategies are found in humanities and language teaching — areas in which girls perform well and with confidence. But they are still foreign to the majority of science teachers.

Science teaching must move away from the rigid, dry-as-dust approach and become more accessible to girls. It needs to incorporate strategies which concentrate on communication and creativity, and to encourage girls to view science as a human activity.

Girls need to see there is no conflict between science and femininity. They need to be presented with female role-models they can relate to.

Girls need to be encouraged at home that science is for them, and learn at school that science is fun, relevant and a vital human activity.